Charcoal Paintings

The pictorial facts that make Safiuddin Ahmed’s each charcoal work on paper looks ‘complete’, are pretty much about the basics – it is a certain type of conformations of lines set against the areas of darkness. The series of works where charcoal lends a definitive character to these black and white imageries takes in many forms, composition-wise. Since lines provide the defining armature of the image, the shapes – or the motifs to be exact – are rendered according to a compositional rhythm that governs each image.

If one looks at how mediums overlap to create a certain desired effect on the surface, one is bound to notice that charcoal work is often overlaid with crayon or some other additional mediums. Because of the meticulous application of charcoal with careful attention to the gradations, the works give a clear indication that they were gradually developed. And the accumulated layers which together give off a sense of ‘quietness’ are their main strength.

These imageries silently encroach on human consciousness. With an accurate articulation of the painterly attitude towards line and nuanced shades overladen with texture, the meteorology they create is primarily that of the nocturnes. They hinge upon a melody dedicated to a passion for the night.

The darkness that pervades them awakens in us a desire to see more. As one survey the series one realizes that some are fully dipped in silence, while others are touched by it, thereby inscribing into the works a nocturnal spirit.

Surveying closely the many variations of the subsequent series of charcoal by the atist, one discovers that these are mostly panoramas – landscapes that slowly reveal places, ponds, and people. Even when the work is a portrayal of a rural potter, as in Potter (2004), there is a strong presence of his surroundings. In similar type of works, nature may have receded to the background. But its presence is felt in the image. To sum up the vitality the works exude, one must say that nature through direct and oblique references, or in symbolic space creation, remains an important point of entry into Safiuddin’s imagery.

When line and shading together assume a life of their own, rendering many motif-driven images into subtle abstraction, the works retreat from the panoramic and stage the rhythm as plain pictorial facts. These works are only few and far between. A prime example of such minimalist ploy is to be found in Tree-2 (2004).

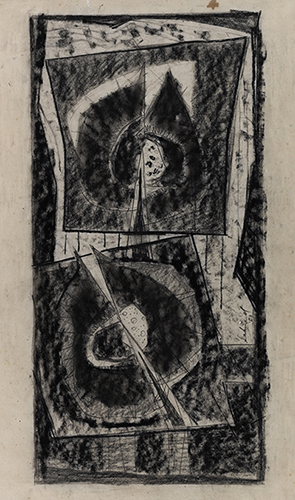

The works entitled Black Series, on the other hand, are many and they exude the nocturnal by way of an obvious geometrical schema. Yet their references are also discernible – the panoramic landscape are presented in an intentionally rhythmic yet fragmented ways.

In some, interconnected forms – looking more like cut-outs – define the very fabric of the image. The constructions, the surface quality as well as the way reference to nature is presented, lend variation to the Black Series. For example, Black Series-14 91994) plates in rough surfaces with a central motif that almost look like an allusion to a flame of a hurricane lamp obstinately burning in the darkest of all hours. Whereas, in Black Series-15 (1994), the boat-like forms and curve lines together create a faint impression of an abstracted landscape. The picture plane is such that any brash strokes would mar the calmness of the image.

Safiuddin had never been an artist who lost sight of the masses. Some of his figural-motifs infused charcoal works testify to this. These are works that present well-lit vistas. In addition, some of these attempt at harnessing both the epic, relating to life, with the epochal, relating to time.

One such epic creation is entitled Floods: The Joy and Sorrows, where the artists depict all the facets of flooding in Bangladesh. It presents a cycle through which the pauperisation of the masses is depicted. If at the foreground a forlorn mother sits with her empty platter, there are scenes in the village where rural life with its predictable happiness and plights are showcased.

What makes one wonder are works that had rarely been given attention by major art writers of the last century. Two Faces (1999), or Floods-7 (2003), are proof that the agony of the people had beseaged the artists from time to time, and the romantic nature had to make way for tortured faces.

The most important writings that emerged in the last twenty or so years on the maestro whose oeuvre is perceived to have been made up of mostly painting in oil and watercolour and etching, had little or no words to spare on the charcoal series. No methodical study of his charcoal works exists through which to evaluate the mutation of forms and style achieved in charcoal. If the bold, geometricised charcoal drawings that preoccupied the artist in the 1970s, it slowly grow into a series of works that seems complete in itself. Perhaps the preparatory drawings for etchings like Remembering Ekushey-3 (1987), or a sketch such as Floods-3 (1992), are works that have prepared the ground for nocturnal pieces that the maestro embarked on two years later. However, there are no apparent relations between the works done in 1992 and in 1994.

The stark yet nuanced black one encounters in the series executed in 2006, has in it pieces that are rhythmically anomalous – they take their cues from nature but attempts an aesthetic equilibrium that stems from the desire to cast them in a sublime composition.

The mastery at work in numerous charcoal series done since the early 1970s, cannot be overemphasised – the lines, the rhythm and the shading in its various different depth and lightness, together suggest a serious intention to produce complete paintings. They give a clear impression that the maestro intended to make them look as if they are standalone paintings rather than preparatory drawings for future paintings or etchings.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist and writer based in Dhaka. He is editor of the upcoming journal A+.