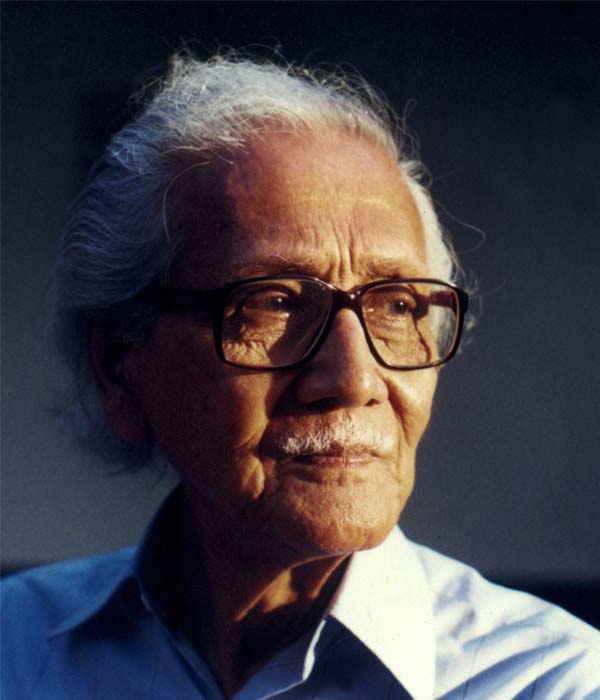

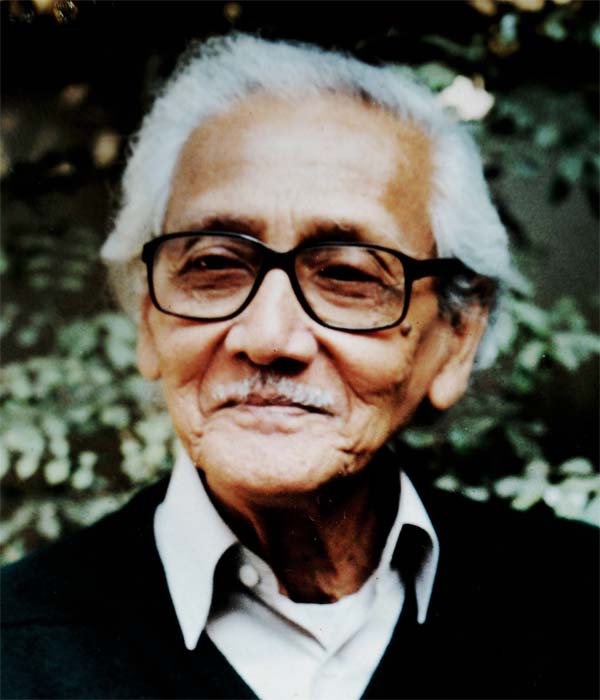

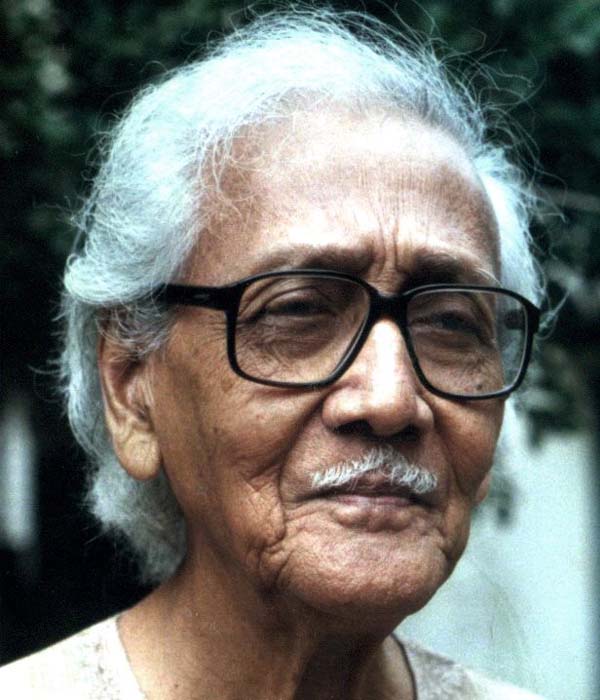

Shilpaguru Safiuddin Ahmed

Between Flooded Landscape and Symbolic Fishes

Safiuddin Ahmed, one of the pioneers of modern art in South Asia, is an underrated artist to have lived and worked in both the twentieth century and the new millennium. His towering achievements in printmaking and painting have always kept him in the conversations of the art cognoscenti. However, there is a great dearth of textual materials focused on his contribution to the visual culture of this region. It is due to such lack that his numerous masterpieces have not enjoyed full public attention. There has been little effort to survey the changing patterns of the linguistic formulation through which Safiuddin kept discovering his own voice during his lifetime. Among the publications that attempted to do so include the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy book as part of their modern masters series on him where Mahmud Al Zaman wrote an apt monograph, and the Bengal Foundation tome on him as part of the Modern Masters of Bangladesh Series followed by the biography by Syed Azizul Haque dedicated to the ace etcher and painter who, like many a great artist, chose to live his life far from the public eye.

Land and people together form the core of the master artist’s vision. Fashioned into a personalised idiom, the recognisable features of places and peoples define the very contours of his idiom, which primarily translated into works of rich formal quality. They were produced using an array of methods and mediums including etching, wood and metal engraving, pencil on paper and oil on board and canvas. The organising principle achieved by way of exploring geometrical and/or natural morphological features, those that governed his myriad work-surfaces, clue us in on the contexts.

Most of his creations resonate with the viewers since they recall the actual experience of the artist. The maestro thus comes off as a witness of natural and social events, those that he harnessed in many of his oeuvres created over a long career that had begun in Kolkata in the early 1940s and later thrived in Dhaka following India’s Partition in 1947.

The oeuvres of this master artist have been a way for him to embody a unified vision centred on man and his habitat. When this etcher cum engraver and painter depicted people living in proximity with nature, he did so with an apparent understanding of nature’s unceasing succour. Like some of his equally well-known peers who also left Kolkata after the partition of India to settle in Dhaka, Safiuddin too had mostly been engaged in celebrating the beauty of nature and the naturalness recognized in the cycle of life.

An artistic language that had shown a noticeable affinity towards a romantic vision evidenced in his early works through his undivided attention to the beauty of the Santal’s way of life lived amidst unspoiled nature, also gradually included human travail, if not the intermittent political violence that forever soured the relationship between Hindus and Muslims. The sectarian violence that rocked the cities across undivided India, with Kolkata as one of the centres of the unfolding tragedy, made Safiuddin visibly perturbed. Like many other artists, he too averted his gaze from such social-political calamities.

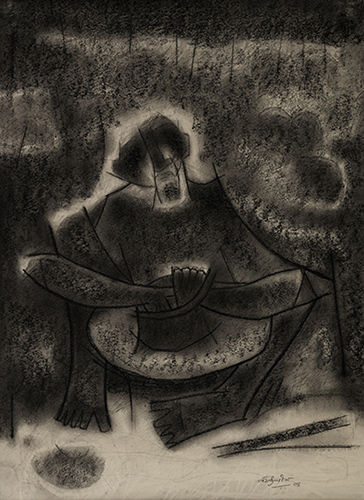

37 x 50cm

1959

He always had his eyes set on an Arcadia. While some had chosen to look at rural spaces as a geography of solace to escape the urban scourge, Safiuddin looked at nature as both an Arcadia to become nostalgic about and a living source of unbound energy. Nature would later appear in a completely different “note” at his behest, one that the Kolkata cognoscenti were unaware of since it pegged its hope on the intensity of colour and the cosmic rhythm of line. By the mid-1950s, Safiuddin would discover a unique rhythm to organize the visual elements on a picture plane to invoke the “musicality” he could sense in nature. This he would accomplish by employing linearity in the service of the composition, by restructuring it according to the emotional dictates, or by suggesting a synthetic kind of spatial construction to evoke man-nature harmony.

As for the man who lost his father when he was only six and was reared by a caring mother, like many a progressive artist of his time, Safiuddin never flinched from becoming part of the conscientious segment of the society responsible for the embryonic voice against colonialism, political polarisation and various other forms of oppression. Besides the spiritual ventilation of emotion through the exploration of nature based on aesthetic means, Safiuddin, a reticent man, in times of need, had taken part in artistic activism. Though he was not a member of the Progressive Writers and Artists Union, as a conscious individual he was inspired by their cause and had occasions to contribute to their might.

As an artist, Safiuddin had to carve out his path to suit his unique taste for visual harmony, which he first discovered in nature and later synthesized into being through references to nature, life and art.

29 x 21cm

1945

Born in 1922, in Kolkata, then a centre of business and art where new cultural effusions brought about hope for freedom and justice for the colonised, Safiuddin Ahmed’s training in art began with the likes of Mukul Dey (1895-1989), Basantakumar Gnaguly (1893-1868) and Ramen Chakravarty (1902-1955), Abdul Moin (1910-1939), providing the much-needed early educational ingredients on which he would later build his career. They were among the most competent teachers of the Calcutta Government School of Art, where the maestro spent six years between 1936 and 1942 to complete a course equivalent to honours. Abdul Moin inspired him to pursue Indian art while others showed him the way to perfect the British academic learning. For his excellence in the academy, he became one of the much-talked-about students of his time. He joined the school as a teacher on the year he completed his study.

Safiuddin’s early works bear all the telltale signs of a naturalist — he developed a habit for venturing outdoors to harness the beauty of nature. His frequent visits to Dumka area of the Santal district, his excursions to the regions of Bihar to capture the beauty of untouched nature have been famously fruitful. There are delicate wood engravings that are now considered masterpieces — they recall the Santal lives he witnessed at Dumka. There are etchings and aquatints that captured the pristine beauty of the panoramic landscape of Dumka and Santiniketan. There are also oil works making visible the play of light on forested land and rural social spaces. If some of these are unpeopled, most are animated with humans traversing the land or roads, or even crowding a bazar. The latter is to be found in a gesture-heavy oil painting entitled Paddy Bazar (1952).

If a roster is made of his early artistic inclinations it will clearly show that like Zainul Abedin, Safiuddin too, in many different ways, sought to make labour visible. The works populated by humans bring to light the activities pertaining to the existing lifestream. The artist depicts the participants in the social processes rather than highlighting the moments of idleness. Though the human forms are dwarfed by the presence of nature in these early landscape works, they are not abstracted from their context. The humans are integral to the stream of life of the region, and these works seem to bring that into light.

32 X 20cm

1988

The most enduring imageries that resulted from such method of representation are found in his depiction of Santal life — the figurative wood engraving series on Dumka executed between 1942 and 1945. These masterpieces testify to Safiuddin Ahmed’s ability to attend to the details and to plumb a sense of longing, thereby reflecting a collective nostalgia for the slowly disappearing wilderness. These are sites of naturalistic intent, and they work as an extension to the Ruskinian concept of observing nature from close quarters. In Safiuddin’s hands, naturalism turns into a creed of idolizing “simple life” lived against an idyllic setting.

There is more than just “idyllic romance” to Safiuddin’s brand of naturalism. The attempts at capturing life and nature in their most intimate relationship, also variously explored by a number of practicing artists of Safiuddin’s time, take the master’s empathetic gaze beyond the concept of situatedness. How the starkness of the method of wood engraving instigated a retooling of naturalism, a concept brought into this land by its modern-day conquerors, the English elites, is a fact that can be read and re-read in Safiuddin’s early, peopled landscapes as well as in his life-celebrating images of the Santals.

The Santal wood engravings tackle different themes under different titles. For example, Santal Women (1946) shows women replenishing their pitchers from a pond, while On the Way to Fair (1947) depicts a fair-going crowd. These are archeogeographies brought forth through the process of memorializing lives lived amidst the enchanting scenic beauty of rural Bengal.

In the context of his rising fame, which had already been sealed through his exploration of delicate engravings and etchings, Safiuddin’s artistic trajectory soon began to speckle into various mediums and schemes. The journey, once traced down to his early infatuation with naturalistic depiction of rural setting, also testifies to his ability to produce emotionally immersive landscape. His Homeward Bound, a wood engraving from 1945, where water buffalos are being herded back home as dusk falls against a majestic landscape, only finds its match in the delicate aquatint on the theme of the river Mayurakkhi (1945). The former attests to his mastery over the medium to articulate every element in silhouette, while the latter makes visible the nuances fitting to the landscape where the lives of the locals thrive on and around the river.

51 x 76cm

1994

After acquiring his degree in 1946, Safiuddin Ahmed soon began to explore imageries where the prevailing fascination with nature were aligned with his acquired thirst for a suitable organisational quality to lend meaning to the observed reality. There was learning from the likes of Abanidranath Tagore, a key figure of the Orientalist movement in Kolkata. However, our maestro, like some of his gifted peers from the new generation, had to eke out a language of his own. He did this by slowly withdrawing from the naturalistic tendency to introduce an artistic strategy based on morphed images and rhythm of lines achieved through a logical division of space. Spatial arrangement thus served as the basic premise for this master, in whose language fishing nets, boats, water bodies, roads and lands canopied by trees easily transformed into personalised imageries.

The move towards symbolism had percolated into recognisably personal idiom as early as in 1954. An oil-on-canvas from that year entitled Sherbet Stall-1 testifies to the emergent language. It takes geometric pattern as its guiding principle and suggests a departure from the naturalism of early years as well as the formal experiment with human forms he plunged into 1950 onward. In the year 1950, one witnesses a radical change in the figures he began to represent in works such as Towing Rope-1 and Fishing, where the signs of new compositional logic are discernible. At this point of time, the artist successfully distanced himself from the naturalism that once governed his realm. With the introduction of formal regour, legible in Sherbet Stall-1, the maestro’s mutation from naturalism to an individual idiom was complete.

As for the works done in 1950, they are brush and ink drawings that were perhaps executed as part of his preparation for larger paintings. The entire series discovered in the artist’s collection displays the trait of flatness arrived at through mostly geometricization of the visual data. The intersecting lines found in these works would become more rhythmic in the coming years.

By the year 1960, Safiuddin Ahmed was ready to enter a new phase of creativity. His works assumed a character that efficaciously married the observable reality with the aesthetical elements — the latter can be defined in relation to the organic and geometric patterns. Even with charcoal or crayon on paper, he could arrive at the new signature Safiuddin idiom — one that he would pursue throughout his life. This idiom assumed many faces and dimensions, at times becoming abstract in character, while mostly remaining faithful to the lived experience.

110 X 70 cm

2005

Between 1947 and 1956, Safiuddin produced only a single work in aquatint, declares Azizul Haque in his monograph on the maestro, in the tome published in 2011 by Bengal Foundation. In 1957, a year after his study in London had begun in 1956, the maestro returned to etching and aquatint. Fishing Time (1957), in a metonymic gesture helped him lent his enthusiasm for themes of water, fish and flooding. They appeared in a entirely new dimension with shapes and lines defining the contours.

In the series that would soon emerge, lines and their rhythmic arrangements opened up the possibility of tackling themes with the ease of an abstractionist. If in the first etching a man becomes the focal point, though, in a rather diminishing frame compared to the sprawling nets around him, in works such as Fisherman’s Dream (1957), Yellow Net (1957), curvilinear forms dictate the work-surface. Boats and fishes thus metamorphosed into patterns in sync with the greater scheme of the desired composition. These are overpoweringly abstract images, or cosmic compositions where the human occupants are pushed out of focus. As a result, space becomes symbolic for the first time.

Human motif reappears in one exceptional copper engraving of 1958. In the work entitled Guntana, or Towing Line, two male figures are morphed into complex tangle of lines. Majestic in their appearance they testify to the master’s exquisite handling of lines, that too in metal engraving, which is one of the most challenging mediums for printmakers?

On the heels of such extraordinary experiment with lines and forms, works such as Floods-1 (1958), or Composition (1958) take Safiuddin’s symbolism further to the region of abstraction. These works would finally lead the maestro to his celebrated series The Angry Fish (1964). Conceived as a protest against the ongoing oppression of the Pakistan junta, the work defines the tenor of his etching and aquatints of the 1960s. Of myriad other ways he would refer to reality, this was one of the most abstract yet potent with the possibility of setting in motion a translatable order of signs.

The deep-etch method helped the artist achieve a unique tactile quality that invites touching. If the series of works that employs similar technique do not work as a window to the scenes they propose, which is often the case with works suggestive of land and water, their sense of depth comes from the thick black lines and shapes.

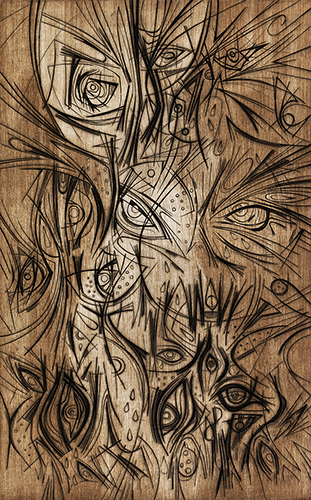

The Angry Fish would later prompt many other images based on the transmuted motif of the eye — a series he launched after 1962 was modelled after this. These works can also be seen in the light of the evolving formal experimentation of the late 1950s. His aquatints on the theme of the floods, or even before that, the series entitled Before the Storm (1958), pulled from the same plate, which, no doubt, had laid the ground for regorious application of repetitive and rhythmic motifs.

“Since his student days, Safiuddin has always had a penchant for black,” declares Syed Azizul Haque in his essay on the master, in the book entitled Safiuddin Ahmed published by the Bengal Foundation. One feels enticed to add that the maestro was also a colourist as is evident in his paintings and etchings of various phases. The Dumka paintings lifted the colours right out of the observable world. If these early landscape works used an earthy palette to depict the immediate reality, in the post-independent phase his oil on canvas works employed various different shades of vibrant green and blue. Even in the London-era prints, one witnesses the insertion of brown and yellow, which lends them a unique artistic verve unparalleled in the history of printmaking in this region. Especially before the appearance of Monirul Islam in the Dhaka art scene around the early 1990s, these were the only works where the profusion of bright hues was found. The brightness of colours and their nuances together sought to express nature’s energy in the master’s works.

As for black used as a medium of “complete absorption of visible light” to affect a sense of depth in prints, Safiuddin’s works serve as an example. While working with metal plates, every printmaker grapples with the problem of density. Safiuddin perhaps had applied black to an enviable effect. His Receding Flood (1959), or In the Grip of Floods of the same year, are works that bring into play a nocturnal sense that enhances the experience of looking at the images.

Between the flooded landscape and the symbolic fishes there are myriad other motifs to discover in Safiuddin Ahmed’s works. It is a well-known fact that he has been a recluse in his life always keeping himself away from the clamours of modern life. But he was also a disciplined teacher at the Institute of Fine Arts, a modern educational space he helped to establish after Pakistan came into being in 1947. Though his unwillingness to yield to popular demand for images and his aversion to regularly sell his works stoked speculations, Safiuddin had never forged a public persona wilfully mystifying his position as artist or educator. He was above any such falsification. His role in establishing the first modern institution often remains unmentioned though he was a founder member of the Government College of Arts and Crafts, which is now Faculty of Fine arts, Dhaka University.

In all likelihood, Safiuddin was not an enigma though he is often portrayed as one by some artists and writers. He was not even a man withdrawn from the usual cycle of life. By the virtue of his meditative engagement with both life and art he developed an evolving trajectory of art where quality, style and subtlety of mediums comingled to create a coherent language of expression. Both the person and the artist are present in his works. To further one’s understanding, one should resort to what Syed Azizul Haque, his biographer, once wrote in the now defunct art journal Depart. “As a leading practitioner of modern printmaking of the region, he is often considered a purist, one who works with the bare minimum with the intention to find a middle ground between the subjective and the objective,” he wrote. Perhaps in his life too, he resides between these two ends of a continuum. Like many other artists who chose to live their lives away from the public gaze, Safiuddin Ahmed’s too seems to have accrued some unnecessary layers of ambiguity. However, his life, words and most of all his art have been as reliable a source for anyone willing to look through the mist to place the master in the context of his time. That he occupies an obvious position of a virtuoso in the history of art is a fact that can easily be discerned from what he has left behind — gems of enduring quality.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist and writer based in Dhaka. He is editor of the upcoming journal A+.